L’Oréal 3D Prints Human Skin in Partnership With University of Oregon

Researchers at the University of Oregon have partnered with scientists from the renowned French skincare company L’Oréal to pioneer the first successful development of an artificial skin model closely resembling natural human skin. This collaborative effort aims to address the need for more accurate testing methods for cosmetics and skincare products, as well as to explore potential medical applications.

The artificial skin, which closely mimics the complexity and structure of natural human skin, is the result of a novel 3D printing technique invented by Paul Dalton, a professor at the university’s Phil and Penny Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact. This innovative method allows for the creation of multilayered skin-like cell colonies in a period of just 18 days.

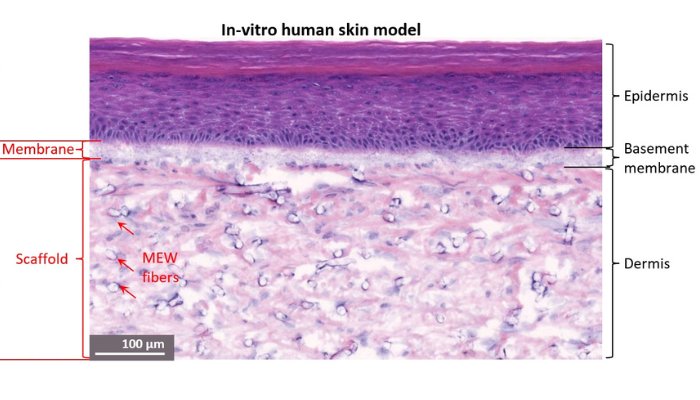

The two-layered artificial skin in-vitro. (Photo Credits: Paul Dalton)

A Two-Layer Approach To Realistic Skin

In the past, replicating human skin has been exceptionally challenging due to its diverse array of cell types and complex extracellular matrix. This matrix is crucial in facilitating cell communication and overall function, presenting significant hurdles in achieving accurate mimicry. However, unlike prior methods, Dalton’s technique can achieve unprecedented realism and functionality.

To effectively mimic the intricate structure of human skin, L’Oréal and the University of Oregon codeveloped a two-layered artificial skin separated by a membrane. They then developed plastic scaffolds that closely resembled the extracellular matrix. These scaffolds, built using finely structured 3D printed threads, provided a foundation for L’Oréal researchers to grow distinct cell types within each layer, preventing intermingling during development with the help of the separating membrane.

Speaking on the successful replication, Dalton stated, “Other attempts don’t have the same layering—it actually looks like real skin.” Researchers at Dalton’s lab have reported that this constitutes the first successful “replicating of quality skin tissue at full thickness.”

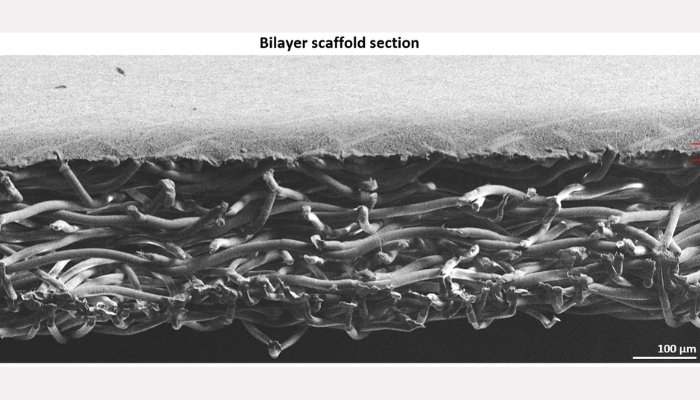

Scaffold section of the full-thickness human skin. (Photo Credits: Paul Dalton)

To create the plastic scaffolds, Dalton and his team turned to melt electrowriting (MEW), a novel 3D printing technique Dalton had previously helped develop. Often used in the medical industry to create porous macrostructures with fine detail from an electrically charged molten polymer, this approach allowed Dalton and his team precise control during printing, enabling the creation of larger skin components without compromising quality.

L’Oréal, leveraging its expertise in skincare research, plans to use the artificial skin model to rigorously test the efficacy and safety of its products. Beyond cosmetic applications, researchers envision a large variety of potential uses for this revolutionary technology, including the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers and the creation of skin grafts for burn patients. Moreover, the scaffold material has sparked talks of utilization for a broader range of biomedical applications, including artificial blood vessels and structures that facilitate nerve regeneration. To learn more about this achievement, click here.

What do you think about this achievement of 3D printed skin between L’Oréal and the University of Oregon? Let us know in a comment below or on our LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter pages! Don’t forget to sign up for our free weekly newsletter here, which has the latest 3D printing news straight to your inbox! You can also find all our videos on our YouTube channel.

*Cover Photo Credits: University of Oregon