Bioprinted artificial tissue to heal bone and cartilage injuries

A team of scientists from Rice University and the University of Maryland in the US are developing 3D printed artificial tissues to help bone and cartilage that has been damaged. This could help injuries, typically induced by sports, including knee, ankle and elbow injuries. The bioscientists designed scaffolding that reproduces the physical characteristics of an oesteochondral lesion (a type of crevice that appears at the surface of cartilage, usually found in the talus or tibia bone). Using the 3D printed uniform and gradient scaffold for bone and osteochondral tissue, the team hopes to offer treatment for this sort of injury.

The recent developments in bioprinting make it possible to understand certain diseases or injuries better. Also, bioprinting allows to find solutions adapted to each patient and their needs. The method involves depositing bio-ink layer by layer. The bio-ink is typically loaded with cells. The procedure can be used to create artificial tissues, organs or cartilage. We are still at the beginning of the technology but the results are promising. There was already the successful bioprinting of a kidney – able to work for 40 days.

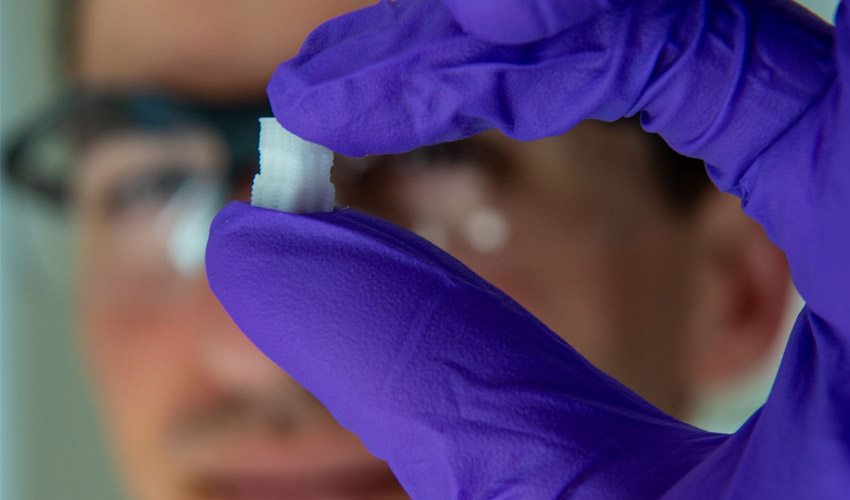

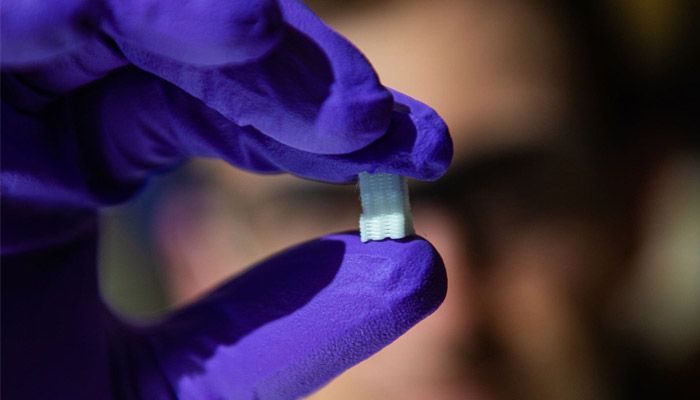

Credits: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

This particular project, led by bioengineer Antonios Mikos, aimed to imitate a tissue that gradually turns from cartilage (chondral tissue) at the surface to bone (osteo). In order to do this, the team of researchers bioprinted a scaffold with custom mixtures of a polymer for the cartilage part and ceramic for the bone part (with imbedded pores to allow the patient’s own cells and blood vessels to infiltrate the implant). Eventually, the scaffold should become part of the natural bone and cartilage, enabling osteochondral lesions to heal.

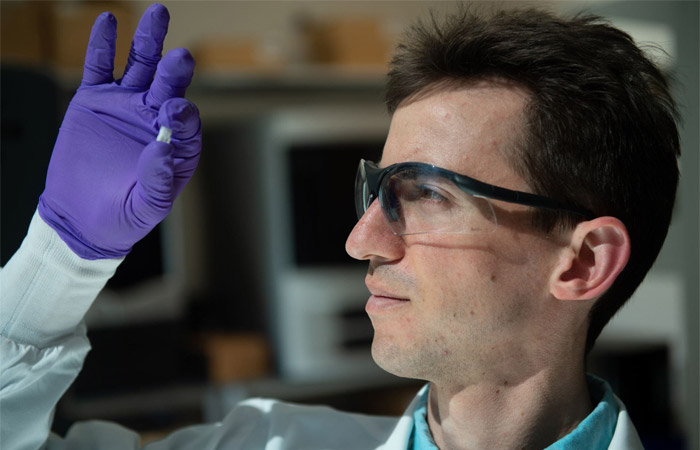

One of Rice University’s students, Sean Bittner, commented, “Athletes are disproportionately affected by these injuries, but they can affect everybody. I think it will be a powerful tool to help people with common sports injuries.” He added, “For the most part the composition of the bio-ink will be the same from patient to patient. There’s porosity included so vasculature can grow in from the native bone. We don’t have to fabricate the blood vessels ourselves.”

Sean Bittner | Credits: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

The next steps in this project should be to determine how to print an osteochondral implant that is perfectly adapted to the patient and that could develop and bind directly to the bone and cartilage. You can find more information HERE.

What do you think of this research? Let us know in a comment below or on our Facebook and Twitter pages! Don’t forget to sign up for our free weekly Newsletter, with all the latest news in 3D printing delivered straight to your inbox!